To comprehend fully what music does for movies, one should see a picture before the music is added, and again after it has been scored. Not only are all the dramatic effects heightened, but in many instances the faces, voices, and even the personalities of the players are altered by the music.Source: Dimitri Tiomkin, "Composing for Films," Films in Review 2.9 (1951): 21. (The full article runs pp. 17-22.)

Thursday, September 8, 2011

Masking Exercise

Here is a quotation from Dimitri Tiomkin that could serve to introduce the masking exercise:

Tuesday, August 30, 2011

Administrative Post

I've just discovered a stash of emails that were sent to the link on the site here. This spring and summer, Google has been transferring the accounts associated with the site, and during that transition, some emails seem not to have arrived immediately. I have now answered all the emails that have appeared in the inbox. If you have sent a message and not received a reply, please resend your inquiry.

We apologize for the confusion.

We apologize for the confusion.

Saturday, August 20, 2011

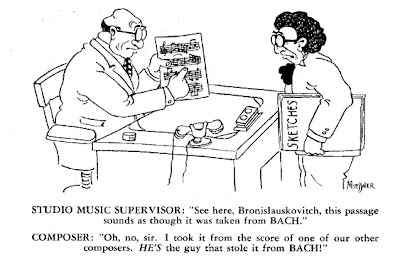

Studio Scene

A little self-deprecating humor from The Score, the official newsletter of the American Society of Music Arrangers.

Image Source: The Score, 2.7-8 (1945) (PDF).

Image Source: The Score, 2.7-8 (1945) (PDF).

Image Source: The Score, 2.7-8 (1945) (PDF).

Image Source: The Score, 2.7-8 (1945) (PDF).

Thursday, August 18, 2011

Marlin Skiles Says...

The American Society of Arrangers and Composers has posted PDFs to four volumes of The Score, the organization's newsletter, from the late 1940s. At the time, the organization claimed membership by the prominent orchestrators and arrangers working in Hollywood. The following, short article by composer and arranger Marlin Skiles is typical of the materials to be found in the newsletter

Among the subscribers to THE SCORE, there are undoubtedly many people who wonder just how the arranger functions in the music profession. Consequently, I think it would be well to give a description of just what the arranger's place is in musical society.

Most of our popular music is written for voice with piano accompaniment. As there are many mediums of performance other than vocal, it is necessary then to have this music transcribed, or re-written so that it is possible to perform it in another manner.

This is the arranger's job. Every time a piece of popular music is performed in any other version than that of voice and piano, an arrangement or orchestration has to be made for the particular way it is to be performed.

The arranging profession came to the fore with the advent of the jazz era, and it is a singularly unique American development. It is a definite expression of the American way of life, caused by the desire for individualism, variety and the demand for something new and different.

A competent arranger is expected to be, among other things, an excellent musician, a clever "idea" man, an inventor of new styles or patterns, and a composer of sorts. He is supposed to shun the thought of imitating any previously employed devices in his idiom.

This, of course, is quite an assignment, and it is remarkable that so many thousands of music writers in this country pass the test. The arranger has become as necessary to our present popular music production as the mouthpiece is to the wind player or the bow to the fiddler.

It can truthfully be said that without the arranger, easily 80 per cent of our popular songs would never have been written. This estimates the percentage of popular songwriters who cannot so much as write their own melodies.

Hence jazz itself would never have risen above the cacophonous state in which it was born, had not the arranger appeared on the scene.

Source: "Marlin Skiles Says," The Score 1.3 (March 1944), 1. (Link is to PDF.)

Image source: Color masthead was excerpted from the cover posted here.

Wednesday, January 12, 2011

YouTube analysis-comparison exercise

The sheer volume of items posted to YouTube makes it easy to construct elementary comparison exercises that draw on audiovisual analysis. The point of the exercise is to give students practice very early in semester (as they read HtM Ch. 1) but isolate the work from the complex narrative contexts of feature films and from the students' learned viewing habits for films.

The task is to describe different visual tracks as they relate to a single audio track. I chose performances of a musical composition because they're easy to find on YouTube and often are relatively stable there (that is, not taken down), but more so because the limits of the musical text allow us to treat the sound track more or less as a control, against which we can more easily compare different collections of images, still and moving. Tempo remains a variable in the audio track as well, of course, but we will minimize that by looking first at three visualizations of the same recorded musical performance.

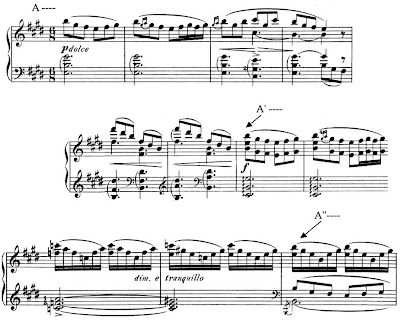

The composition is "Morgenstimmung" (Morning Mood), the first movement in Edvard Grieg's Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, Op. 46. The design is simple: A - A' (expanded) - A'' (as coda or ending section). Here are the corresponding moments in musical notation (piano reduction only).

Timings for the three sections in the performance by the Berlin Philharmonic under Herbert von Karajan are included at the top of the next example, which charts the principal harmonic changes through the movement. (The image is a thumbnail -- click on it to see the original.)

Version no. 1: link. [Link is broken; checked on 3-08-2024.] One might think of this as a "control" since the image track is static, nothing but a title card. In fact, however, this is in some ways the most difficult version to study because the students must be able to pay attention to their attention, so to speak. Once they guess that the image is probably not going to change, attention shifts away from it to the music, in a radical version of what Claudia Gorbman calls the "pure cultural musical code," that is, music as performance. A clever student who refuses the let the image track go entirely may relate the starkness of the black background to the audiovisual sparseness of a video that is only music.

Version no. 2: link. [Link is broken; checked on 3-08-2024.] The same recording (played twice!) with a slide show of images. Questions to consider: how are changes to a new image timed to the music track? (Generally, they avoid synchronization -- images change shortly before the downbeat of a new bar. Exceptions @ about 2:40.) What is the effect of the lack of synchronization @ important form articulations in the music? (If images had changed at those moments, the images would suddenly have seemed relatively "important", leading to speculation about reasons for that importance. Something similar happens in a couple cases where the slide is onscreen noticeably longer than the others.) What kind of narrative content (or expectation for narrative continuity) is provoked by the slide show? (The obvious one would be the minimal narrative of dawn in many different locales -- but here again there are a few exceptions, slides that obviously depict mid-day. One might also ask whether chronological continuity is important -- one slide of a darkened tree and a pre-dawn planet seems out of place. In the case of narrative, it is not important to come up with answers -- what is important is to notice the fact of imposing (or trying to impose) narrative continuity on the images.) The ending of the first playthrough is obviously clumsy in the image track (the photo of Grieg appears twice in short order and then the slide show starts up a third time a few seconds before the piece ends).

Version 3: link. [Link checked on 3-08-2024.]An upgrade to the slide show that makes a very good comparison for no. 2. Here the poster is playing with simple effects applied to a video of a fire in a fireplace. Because the editing is plainly done by someone (no. 2's slide show could have been an app on autopilot), the questions of intention and design arise more seriously. (If students know about it, a discussion of the associations brought up by the context of the YouTube "Kaminfeuer" trope could be interesting -- here again, it's not the information that is important but the realization of the power of these external associations to shape or guide the viewing -- very much like genre expectations in feature films.)

Version no. 4: link. [Link checked on 3-08-2024.]Not Karajan. By comparison with no. 2, both performance and slide show seem frenetic.

Version no. 5: link. [Link is broken; checked on 3-08-2024.] Here is what Gorbman really meant by the "pure" code in feature films: a filmed performance of the piece by an orchestra. The camera is static. Compare to this performance that has multiple cameras and was edited: link.

The task is to describe different visual tracks as they relate to a single audio track. I chose performances of a musical composition because they're easy to find on YouTube and often are relatively stable there (that is, not taken down), but more so because the limits of the musical text allow us to treat the sound track more or less as a control, against which we can more easily compare different collections of images, still and moving. Tempo remains a variable in the audio track as well, of course, but we will minimize that by looking first at three visualizations of the same recorded musical performance.

The composition is "Morgenstimmung" (Morning Mood), the first movement in Edvard Grieg's Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, Op. 46. The design is simple: A - A' (expanded) - A'' (as coda or ending section). Here are the corresponding moments in musical notation (piano reduction only).

Timings for the three sections in the performance by the Berlin Philharmonic under Herbert von Karajan are included at the top of the next example, which charts the principal harmonic changes through the movement. (The image is a thumbnail -- click on it to see the original.)

Version no. 1: link. [Link is broken; checked on 3-08-2024.] One might think of this as a "control" since the image track is static, nothing but a title card. In fact, however, this is in some ways the most difficult version to study because the students must be able to pay attention to their attention, so to speak. Once they guess that the image is probably not going to change, attention shifts away from it to the music, in a radical version of what Claudia Gorbman calls the "pure cultural musical code," that is, music as performance. A clever student who refuses the let the image track go entirely may relate the starkness of the black background to the audiovisual sparseness of a video that is only music.

Version no. 2: link. [Link is broken; checked on 3-08-2024.] The same recording (played twice!) with a slide show of images. Questions to consider: how are changes to a new image timed to the music track? (Generally, they avoid synchronization -- images change shortly before the downbeat of a new bar. Exceptions @ about 2:40.) What is the effect of the lack of synchronization @ important form articulations in the music? (If images had changed at those moments, the images would suddenly have seemed relatively "important", leading to speculation about reasons for that importance. Something similar happens in a couple cases where the slide is onscreen noticeably longer than the others.) What kind of narrative content (or expectation for narrative continuity) is provoked by the slide show? (The obvious one would be the minimal narrative of dawn in many different locales -- but here again there are a few exceptions, slides that obviously depict mid-day. One might also ask whether chronological continuity is important -- one slide of a darkened tree and a pre-dawn planet seems out of place. In the case of narrative, it is not important to come up with answers -- what is important is to notice the fact of imposing (or trying to impose) narrative continuity on the images.) The ending of the first playthrough is obviously clumsy in the image track (the photo of Grieg appears twice in short order and then the slide show starts up a third time a few seconds before the piece ends).

Version 3: link. [Link checked on 3-08-2024.]An upgrade to the slide show that makes a very good comparison for no. 2. Here the poster is playing with simple effects applied to a video of a fire in a fireplace. Because the editing is plainly done by someone (no. 2's slide show could have been an app on autopilot), the questions of intention and design arise more seriously. (If students know about it, a discussion of the associations brought up by the context of the YouTube "Kaminfeuer" trope could be interesting -- here again, it's not the information that is important but the realization of the power of these external associations to shape or guide the viewing -- very much like genre expectations in feature films.)

Version no. 4: link. [Link checked on 3-08-2024.]Not Karajan. By comparison with no. 2, both performance and slide show seem frenetic.

Version no. 5: link. [Link is broken; checked on 3-08-2024.] Here is what Gorbman really meant by the "pure" code in feature films: a filmed performance of the piece by an orchestra. The camera is static. Compare to this performance that has multiple cameras and was edited: link.

Tags:

Claudia Gorbman,

comparison,

exercise,

Grieg,

pedagogy,

YouTube

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)